Cirium Ascend Consultancy is trusted by clients across the aviation industry to provide accurate, timely, and insightful aircraft appraisals. The team provides the valuations and analysis the industry relies on to understand the market outlook, evaluate risks and identify opportunities.

Discover the team’s industry reports & market commentaries. Read their latest expert analysis, viewpoints and updates on Thought Cloud.

Thomas Kaplan, Senior Valuations Consultant, Cirium Ascend Consultancy

News that AirAsia had signed for up to 70 A321XLRs earlier this month certainly raised eyebrows. An airline that already has such a large backlog, and which is still emerging from restructuring, should not, on the face of it, be adding more orders. Reading beyond the headlines, however, the 70 A321XLRs are only commitments, not firm orders. AirAsia Group’s firm orderbook stands at 402 aircraft, all A321neos (including 20 XLRs) save for 15 A330neos. Its in-service passenger fleet comprises only 219 aircraft (mostly A320-family jets, plus 24 A330neos), which is still fewer than the 240+ it was operating in 2019.

In 2015, we prepared a slide deck showing the airlines in Asia-Pacific that had orderbooks far larger than their in-service fleets. Two airlines were outliers: Lion Air and AirAsia. Our message at the time was these airlines had managed double-digit growth rates in the past and it was theoretically possible for them to absorb their orderbooks if they managed to continue the same growth trend.

There were reasons to be optimistic about Southeast Asia’s air travel market. The 640 million people spread across islands and narrow peninsulas were getting richer and they’d sooner or later take a flight. Tourism was booming, and it seemed Chinese tourists would provide an endless source of demand. The ultra low-cost carrier (ULCC) model applied by AirAsia and Lion Air was seen as the best way to capture and drive that growth.

Ultimately, the story of fast-paced growth was not to last. Economic and geopolitical factors along with the competitive dynamics of a ULCC turf war all contributed to a decade of slowed growth.

The chart below shows the compound annual growth rate of the in-service narrowbody passenger jet fleet of Southeast Asian airlines with the largest orderbooks, compared with the region’s overall fleet growth. Looking at five-year periods (but shifting 2020 to 2019 in order to isolate pre-pandemic figures), we can see 2005-2015 was a time of very rapid growth for AirAsia and Lion Air with sustained periods of over 20% annual growth. The Southeast Asian fleet also grew at around 10% per year throughout that decade.

The period of 2015-2019 brought a marked reduction, to single-digit levels, with AirAsia’s narrowbody fleet growing at the same pace as the rest of the region’s fleets. VietJet, which was Vietnam’s ULCC, tripled in size from 24 to 76 aircraft, but added fewer aircraft than Lion Air did and only slightly more than AirAsia.

Since 2019, growth has been a struggle for all these players. Over the past six years, the Southeast Asian narrowbody jet fleet actually shrunk at a rate of 1% per year, and the highest ULCC compound annual growth rate was VietJet’s 3%, a far cry from the >20% the region’s high-flyers had achieved in the past.

Filters: Narrowbody jets, passenger usage, years calculated as 1 July, company category Airlines. Southeast Asia is defined as: Brunei, Cambodia, East Timor, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam.

Source: Cirium Fleets Analyzer

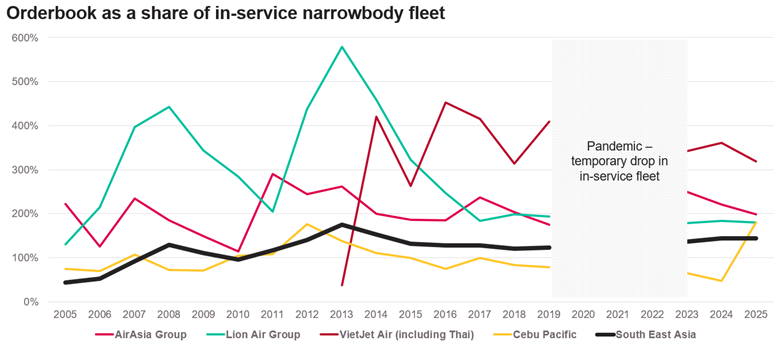

The stalled growth raises questions about the remaining substantial orderbook. Southeast Asian Airlines have 1,366 narrowbody passenger jets on order, representing 144% of the current in-service fleet. By comparison, the world’s backlog share of in-service narrowbody fleet is only 66%. Large Southeast Asian ULCCs’ backlog can be 180% to over 300% of their in-service fleets, which are about the same level as they were 10 years ago. The chart below shows this, while omitting the pandemic years in which the temporary parking of aircraft led to a small in-service fleet, artificially inflating orderbook share.

Filters: Narrowbody jets, passenger usage, years calculated as 1 July, company category Airlines. Southeast Asia is defined as: Brunei, Cambodia, East Timor, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam.

Source: Cirium Fleets Analyzer

Southeast Asian airlines are not taking deliveries fast enough to make a dent in their orderbooks and bring them back to stable levels. Supply chain issues that have been plaguing the industry are partially to blame, but the slowing fleet growth began before the pandemic and the Max grounding. Southeast Asia’s peak for passenger narrowbody jet deliveries was back in 2014 at 126. That is more than has been delivered since the start of 2020.

A replacement cycle rather than a growth cycle may finally drive deliveries, but there are problems with orders placed so far in the past. AirAsia placed a massive order for 200 A320neos back in 2011. To date, only 55 A320neo family aircraft have been delivered to the group. It may have received a good deal from Airbus at the time, but what does 14+ years of escalation do to delivery pricing? Orders were likely renegotiated during the pandemic as the group also went through general restructuring, but escalation continues to increase the eventual delivery pricing.

Southeast Asia is not the only place with a very large narrowbody jet orderbook as a share of in-service fleets. India, Saudi Arabia and Hungary (home to Wizz Air) stand out with orderbook shares at over 200%. It can be argued these have growth potential in different ways, but the ULCCs of Southeast Asia appear to have over-ordered given the trend of the last decade.

This does not risk causing global oversupply, as OEMs cannot deliver fast enough to meet the global demand in any case. However, the backlog increases the risk for those airlines with growing liabilities in terms of escalating delivery pricing in an ultra-competitive market which appears not to be growing as fast as their ambitions.